We have recently published a paper titled “The mitigating role of ecological health assets in adolescent cyberbullying victimization”

in Youth & Society.

Cyberbullying can be defined as bullying which take place in

the virtual world (for example via messaging services, social networking sites,

emails and gaming websites), and can include a number of behaviours such as

sending abusive messages, posting embarrassing or altered photographs, purposely

excluding people from online groups and setting up fake online profiles1.

Cyberbullying has been shown to have a detrimental effect on

young people’s health and wellbeing and their social outcomes. Young people who

are cyberbullied are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, feelings of

loneliness and low self-esteem2,3; research has also identified a

link between being cyberbullied and poorer outcomes at school3.

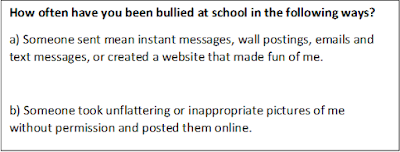

Questions to measure cyberbullying were first added to the

HBSC survey in 2014. You can read our previous blog post which describes why

cyberbullying warranted attention in the HBSC study by clicking here. Cyberbullying was measured by two questions which addressed different forms of

cyberbullying (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Questions measuring cyberbullying in the 2014 HBSC survey |

The prevalence of cyberbullying, and bullying more broadly,

has been reported extensively in the 2014 HBSC England national report4. Of the young people who participated in the

2014 HBSC survey in England, 18% reporting experiencing some form of

cyberbullying in the past two months. Reporting cyberbullying was more common

among girls than boys, and the likelihood of being victimised in this was appeared to increase with age for all

young people (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2. Prevalence of cyberbullying (graph original published in Brooks et al. (2015)) |

Traditionally the health and wellbeing of young people has

been approached from a deficit perspective; this approach asks why young people

are ill and has often focussed on risk factors such as substance use5.

However more recently asset based

approaches have begun to emerge; asking what makes young people healthy and identifying

protective factors which sustain health6. The HBSC

England team are keen to take a positive rather the deficit approach to young

people’s health.

The data collected from the HBSC study is ideal for

approaching health in this manner as it situates young people’s health in its

social context, with the HBSC England survey asking young people about their

family, friends, peers, school and neighbourhood. Work from the research team

has explored protective factors of young people’s health in relation to risk

behaviours7, body image8 and self-harm9. (Check

out our recent blog post summarising our self-harm publication by clicking here).

Our latest paper on cyberbullying uses a similar positive perspective,

and sought to identify elements from the different domains in young people’s

lives, including family, school and neighbourhood, which may protect against

cyberbullying.

The analysis highlighted eight key factors which were

associated with cyberbullying. Factors were identified at the individual level

(gender, age, autonomy), family (family affluence, family communication),

school (sense of belonging to school, teacher support) and neighbourhood

environments (perception of local area). Unlike the more traditional forms of

bullying which are often restricted to the school grounds cyberbullying can

continue beyond the school environment and school hours. Despite this, our

recent paper emphasises the important role the school may play in preventing

cyberbullying; young people who reported positive perceptions of the school

environment and supportive teacher-student relationships were significantly less

likely to say they had been cyberbullied.

The full paper can be found by clicking here.

If you are interested in the topic of bullying you may also like to read our

international collaborative paper presenting cross-cultural trends in bullying

victimization between 2002-2010 by clicking here.

1. Bullying UK. What is cyberbullying? Retrieved October,

12, 2016 from http://www.bullying.co.uk/cyberbullying/what-is-cyberbullying/

2. Wang, J.,

Nansel, T. R., & Iannotti, R. J. (2011). Cyber and traditional bullying: Differential association with depression.

Journal of Adolescent Health, 48(4), 415–417.

3. Tsitsika,

A., Janikian, M., Wójcik, S., Makaruk, K., Tzavela, E., Tzavara, C., …

Richardson, C. (2015). Cyberbullying victimization prevalence and associations with internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents in six European countries. Computers

in Human Behavior, 51, 1–7.

4. Brooks, F., Magnusson, J., Klemera, E., Chester,

K., Spencer, N., & Smeeton, N. (2015). HBSC England national report:

Findings from the 2014 HBSC study for England. Hatfield, UK: University of

Hertfordshire. Retrieved October, 12, 2016 from http://www.hbscengland.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/National-Report-2015.pdf

5. Department of Health. 92010). Health lives,

healthy people: our strategy for public health in England. Retrieved October,

12, 216 from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216096/dh_127424.pdf

6. Whiting,

L., Kendall, S., & Wills, W. (2012). An asset-based approach: An alternative health promotion strategy?

Community Practitioner, 85(1), 25–28.

7. Brooks, F., Magnusson, J., Spencer, N., &

Morgan, A. (2012). Adolescent multiple risk behaviour: An asset approach to the role of family, school and community.

Journal of Public Health, 34(S1), 48–56

8. Fenton, C., Brooks, F., Spencer, N. H., &

Morgan, A. (2010). Sustaining a positive body image in adolescence: An assets-based analysis.

Health and Social Care in the Community, 18(2), 189–198.

9. Klemera, E., Brooks, F. M., Chester, K. L.,

Magnusson, J., & Spencer, N. (2016). Self-harm in adolescence: protective health assets in the family, school and community.

International Journal of Public Health.

No comments:

Post a Comment